Americans are increasingly foregoing paychecks due to disability, school or retirement

by Kasia Klimasinska

How come more people are retiring in their early 20s? Why are middle-age men becoming stay-at-home dads? What’s keeping women out of the workforce other than illness, kids or school?

Those are some of the questions raised in a new Bureau of Labor Statistics report that shows changes over the past decade in why people stay out of the labor force. Finding answers is key for the Federal Reserve as it maps the contours of a job market that’s becoming harder to predict with the aging of the baby boomers and shifting household priorities.

Here’s what the bureau found, broadly: Thirty-five percent of the U.S. population wasn’t in the labor force in 2014, up from 31.3 percent a decade earlier. (You’re considered out of the workforce if you don’t have a job and aren’t looking for one. That’s distinct from the official unemployment rate, which tracks those out of work who are actively job hunting.)

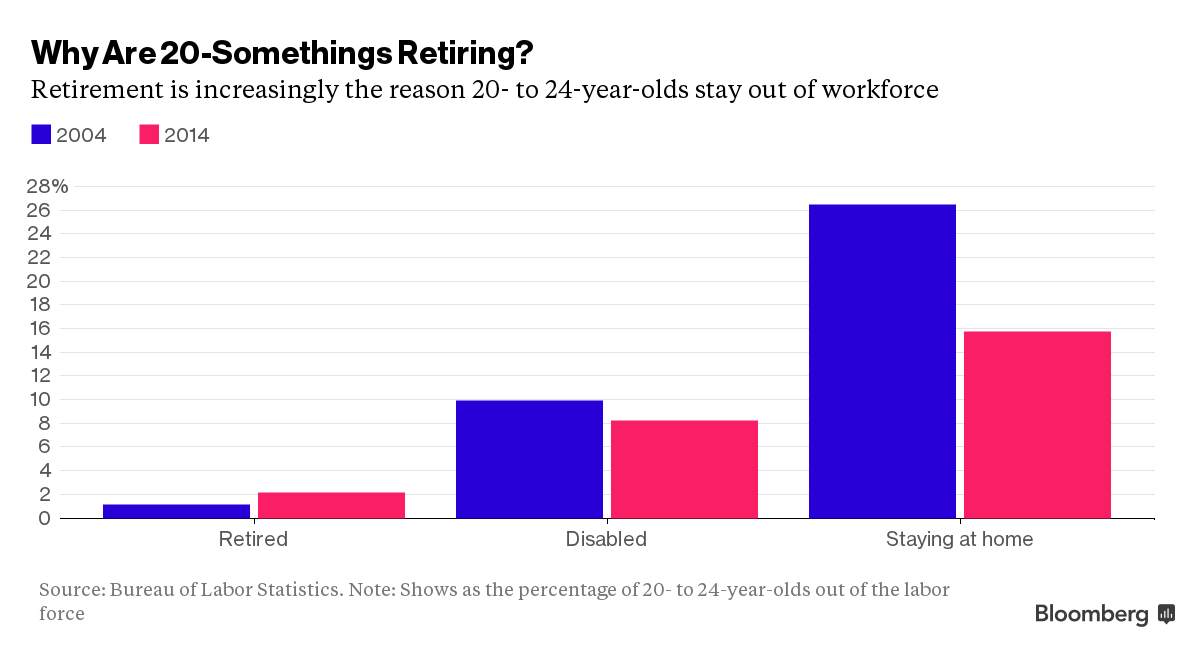

Drilling down into the numbers reveals more about the shifts in the reasons some people forego a paycheck. In all age groups, for instance, more people cited retirement as the reason for being out of the labor force, and it wasn’t just older people.

For Americans between the ages of 20 and 24, the share of those sidelined over the past decade because they were in school increased, unsurprisingly, during the decade that included the Great Recession. What’s more unusual is that the share of 20- to 24-year-olds who say they’re retired doubled from 2004 to 2014.

Other reasons for not working are also on the rise. More men between 25 and 54 cited home responsibilities, while women of the same age range increasingly point to illness or school as the leading cause. The data also show, perhaps not surprisingly, that men and women without a high-school diploma are more than three times as likely to be out of the workforce than their peers with a college degree.

Demographic changes aren’t the only pieces of the puzzle that have changed the employment landscape since 2004. The BLS report showed that among male veterans between 25 to 54 years old, the number who reported a service-connected disability rose to 1.2 million in 2014, from 726,000 in 2003. That rise coincides with U.S. military combat in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Fewer people willing or able to take a job might eventually cause a shortage of workers, leading to surge in wages and longer-term inflationary pressures, according to Princeton University economist Alan Blinder, a former Fed vice chairman.

“We’re going to be running out of labor as we go through time,” Blinder said on Bloomberg Television Dec. 31.

Understanding why people aren’t in the workforce — and whether it’s permanent or temporary — is important for the Fed. Policy makers are trying to estimate remaining slack in the labor market and the outlook for inflation as they weigh the timing of the next interest-rate increase.

But as Chair Janet Yellen told a press conference on Dec. 16, after the central bank lifted rates for the first time since 2006, it may be a while before Fed policy has to contend with an actual labor shortage.

“The labor-force participation rate is still below estimates of its demographic trend, involuntary part-time employment remains somewhat elevated, and wage growth has yet to show a sustained pickup,” she said.

Officials will get more information when the Labor Department releases December’s payroll report on Friday. Economists surveyed by Bloomberg News expect that employers added 200,000 last month, compared with 211,000 in November, while unemployment rate probably stayed at 5 percent.