On February 8, 2021, the Financial Times published an op-ed authored by Eric Schmidt titled US’s Flawed Approach to 5G Threatens Its Digital Future. In it, Mr. Schmidt makes a series of claims, but his central theme is that the U.S. is not doing enough to promote our 5G infrastructure and, worse, forcing us to forfeit the U.S.’s dominant position in the race to 5G to China. He even goes as far as to suggest that the U.S. should throw the proverbial baby out with the bathwater by adopting a more nationalized approach to 5G vis-a-vis the Department of Defense (DoD) spectrum sharing plan. In this article, I address the most glaring of his assertions to put the 5G debate in the proper context.

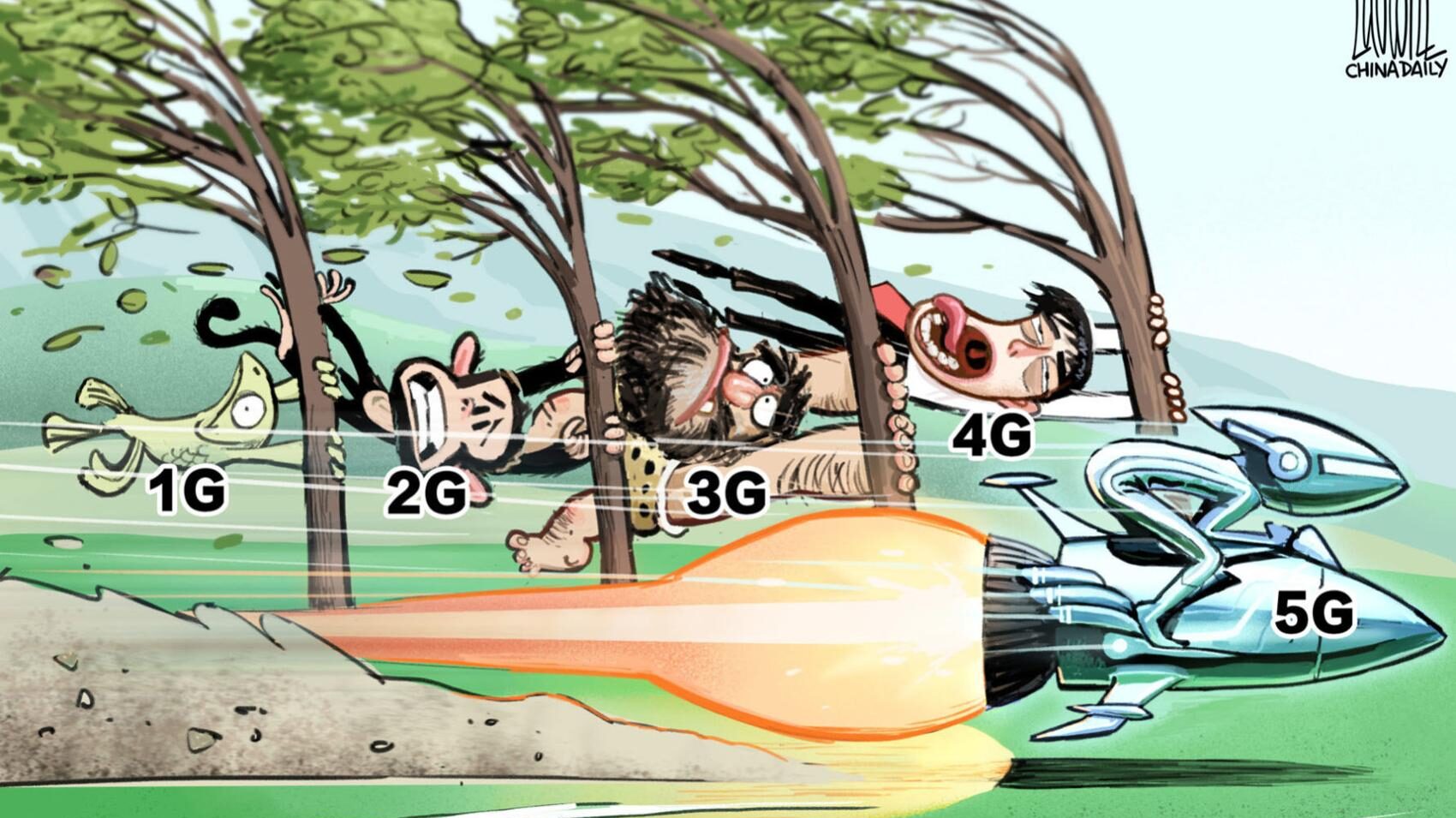

Claim: “…China, is already far ahead [in 5G].”

Response: Mr. Schmidt’s article does not provide a metric when he says that China is “far ahead.” Based on the article, it appears that Mr. Schmidt might be comparing the two countries in the following ways: 1) internet speeds; and 2) national 5G coverage. In each case the United States is excelling. Although both countries have taken very different approaches to 5G, both countries’ 5G strategies involve blending their 4G/LTE networks with their nascent 5G networks. Hence, it is appropriate to compare the countries’ progress on those measures.

In terms of broadband speeds, China has an average internet speed of just 105.2 mbps where the United States has an average of 124.1 Mbps. In terms of broadband speed, we are far ahead of China. Moreover, a study conducted by Global Wireless Solutions released network performance testing from Super Bowl LV in Tampa and found that all three of the nation’s carriers averaged more than 1 gigabit per second on their respective 5G networks, which for the uninitiated means that we have past light speed and are now entering into ludicrous speed. Hence, we are certainly leading in this area.

In terms of 5G coverage, China appears to be deploying far more infrastructure than the U.S., but basing China’s success in 5G purely on the amount of infrastructure deployed may be misguided. The main issue China is having is making its 5G infrastructure compatible with its 4G/LTE networks. This issue is so prevalent that Huawei’s Ryan Ding described China’s 5G rollout as “fake, dumb, and poor,” because most of the applications China is calling 5G is really just disrupted 4G due to the frequent and sporadic handover between the two networks. This is distinct from the U.S.’s plan where it and its carriers have a slower deployment strategy to ensure that its 5G networks can efficiently interoperate with its 4G/LTE networks. However, China’s aggressive 5G policy should be taken seriously, but we should not assume that China is in fact “ahead” of anyone.

The one place where China may pose a competitive threat is in spectrum. This is because China can more easily clear incumbents from spectrum bands for 5G due to its heavier regulatory control when it comes to property rights. Also, China has much more local zoning control over deployment. It is similar to its government’s control on spectrum where it relies on heavy centralized state control allowing quicker infrastructure deployment without public input. If the U.S. wanted to emulate China’s approach, then Mr. Schmidt is essentially advocating that the U.S. allow the FCC to clear bands with disregard to the property rights of incumbents operating in those bands.

Claim: The FCC’s C-Band Auction is a “digital setback,” because the auction provided “no meaningful requirement to build necessary network infrastructure.”

Response: This criticism is simply untrue. As it relates to its C-Band Order, the FCC requires C-Band licensees to meet multiple performance metrics based off of the service or services the provider wishes to provide. For example, In paragraph 93 of the C-Band Order, the FCC requires licensees in the A, B, and C Blocks offering mobile or point-to-multipoint services must provide reliable signal coverage and offer service to at least 45% of the population in each of their license areas within eight years of the license issue date (i.e., first performance benchmark), and to at least 80% of the population in each of their license areas within 12 years from the license issue date (i.e., second performance benchmark). These population benchmarks are actually more aggressive than those for other flexible-use services under part 27 of the FCC’s rules.

There are even performance metrics for licensees providing IoT-type fixed and mobile services on paragraphs 97-99. The C-Band Order requires licensees providing Fixed Service in the A, B, and C Blocks band to demonstrate within eight years of the license issue date (first performance benchmark) that they have four links operating and providing service, either to customers or for internal use, if the population within the license area is equal to or less than 268,000. If the population within the license area is greater than 268,000, the FCC requires a licensee relying on point-to-point service to demonstrate it has at least one link in operation and providing service, either to customers or for internal use, per every 67,000 persons within a license area. The FCC requires licensees relying on point-to-point service to demonstrate within 12 years of the license issue date (final performance benchmark) that they have eight links operating and providing service, either to customers or for internal use, if the population within the license area is equal to or less than 268,000. If the population within the license area is greater than 268,000, the C-Band Order requires a licensee relying on point-to-point service to demonstrate it is providing service and has at least two links in operation per every 67,000 persons within a license area.

Claim: “Future auctions must set stringent build requirements, with penalties for underperformance.”

Response: In paragraphs 102-103 the C-Band Order goes into detail about the penalties for each licensee for not meeting the performance metric. For example, the C-Band Order outlines that, in the event a particular licensee fails to meet its performance benchmark, the licensee will have its license term substantially reduced and, when the shortened term is exhausted, the C-Band Order states that “licensee’s spectrum rights would become available for reassignment pursuant to the competitive bidding provisions of section 309(j) [of the Communications Act of 1934 that articulates restrictions on spectrum license applications] and any licensee who forfeits its license for failure to meet its performance requirements would be precluded from regaining the license.”

Claim: “Pursue alternatives to auctions.”

Response: Mr. Schmidt’s statement is myopic as auctions are only one way the U.S. has advanced 5G. His article failed to review or even mention the myriad of 5G policies in place now. In fact, the U.S. has taken an holistic approach to advance our 5G networks through: 1) a series of subsidy programs (e.g., Rural 5G Fund, RUS Fund, USF programs, etc.); 2) clearing spectrum and auctions (e.g., 24 GHz Auction, CBRS, Ligado Order, and, yes, the C-Band auction); 3) granting key mergers (e.g., T-Mobile-Sprint, AT&T-Time Warner, etc.); and 4) lowering regulatory burdens for wireless infrastructure (e.g., 5G Upgrade Order, 5G Small Cell Order, One Touch Make Ready Order, 6409 Order). Again, Mr. Schmidt fails to mention or even allude to these policies focused on infrastructure.

Claim: “The defense department has proposed sharing government-controlled spectrum with commercial providers if they build infrastructure quickly.”

Response: Mr. Schmidt’s endorsement of the DoD’s proposal is misguided.As I and others have argued before, the DoD’s blue-chip in 5G is that it sits on most of our Nation’s valuable mid-band spectrum, which is essential for 5G deployment. This is clearly evident from every other countries’ inclusion of these frequencies in their respective 5G plans. This is especially true in the case of China that is a leader in mid-band spectrum deployment for 5G. The DoD’s frequencies in its RFI (i.e., 3450-3550 MHz) are prime “beachfront” mid-band spectrum and are critical to open up for commercial use. This is because U.S. commercial 5G networks are severely lacking in mid-band spectrum; a fact of which the DoD is well aware. DoD’s offer to industry is, thus, enticing, but it comes at a hefty price: every carrier must go through the DoD to access this mid-band spectrum that they all will need to make their networks functional. This is a Hobson’s choice for carriers: either they want a functioning 5G network or not. Hence, they will be compelled to work with DoD if this proposal moves forward. This will most likely translate into the DoD being yet another bureaucratic barrier of entry for carriers looking to deploy 5G, which, in turn, slows down the deployment that Mr. Schmidt says the DoD’s plan will promote.

Conclusion

In his article, Mr. Schmidt makes assertions that are either exaggerated, myopic, or confused on the issues of 5G. We can both agree that China’s growth in the area is concerning. However, the arguments Mr. Schmidt presents regarding our auctioning process are not at all the issue and, ironically, is an example of the U.S.’s success in this technological race.

• • • • • • • • • •

Joel L. Thayer is an attorney with Phillips Lytle LLP and a member of the firm’s Telecommunications and Data Security & Privacy Practice Teams. Prior to joining Phillips Lytle, he served as Policy Counsel for ACT | The App Association, where he advised the Association and its members on legal and regulatory issues concerning spectrum, broadband deployment, data privacy, and antitrust matters. Prior to ACT, he also held positions on Capitol Hill, as well as at the FCC and FTC. The views expressed here are his own and do not reflect those of Phillips Lytle LLP, or the firm’s clients.