In a famous essay, the philosopher Isaiah Berlin borrowed a distinction from the ancient Greek poet Archilochus: “The fox knows many things, but the hedgehog knows one big thing.”

“There exists,” wrote Berlin, “a great chasm between those, on one side, who relate everything to … a single, universal, organizing principle in terms of which alone all that they are and say has significance” — the hedgehogs — “and, on the other side, those who pursue many ends, often unrelated and even contradictory” — the foxes.

Berlin was talking about writers. But the same distinction can be drawn in the realm of great-power politics. Today, there are two superpowers in the world, the U.S. and China. The former is a fox. American foreign policy is, to borrow Berlin’s terms, “scattered or diffused, moving on many levels.” China, by contrast, is a hedgehog: it relates everything to “one unchanging, all-embracing, sometimes self-contradictory and incomplete, at times fanatical, unitary inner vision.”

Fifty years ago this July, the arch-fox of American diplomacy, Henry Kissinger, flew to Beijing on a secret mission that would fundamentally alter the global balance of power. The strategic backdrop was the administration of Richard Nixon’s struggle to extricate the U.S. from the Vietnam War with its honor and credibility so far as possible intact.More fromArchegos Appeared, Then VanishedHedge Fund or Billionaire? For Tribune, It’s a No-BrainerIllinois Owes Georgia Voters a Debt of GratitudeOne Cheer for the Return of Earmarks

The domestic context was dissension more profound and violent than anything we have seen in the past year. In March 1971, Lieutenant William Calley was found guilty of 22 murders in the My Lai massacre. In April, half a million people marched through Washington to protest against the war in Vietnam. In June, the New York Times began publishing the Pentagon Papers.

Kissinger’s meetings with Zhou Enlai, the Chinese premier, were perhaps the most momentous of his career. As a fox, the U.S. national security adviser had multiple objectives. The principal goal was to secure a public Chinese invitation for his boss, Nixon, to visit Beijing the following year.

But Kissinger was also seeking Chinese help in getting America out of Vietnam, as well as hoping to exploit the Sino-Soviet split in a way that would put pressure on the Soviet Union, America’s principal Cold War adversary, to slow down the nuclear arms race. In his opening remarks, Kissinger listed no fewer than six issues for discussion, including the raging conflict in South Asia that would culminate in the independence of Bangladesh.

Zhou’s response was that of a hedgehog. He had just one issue: Taiwan. “If this crucial question is not solved,” he told Kissinger at the outset, “then the whole question [of U.S.-China relations] will be difficult to resolve.”

To an extent that is striking to the modern-day reader of the transcripts of this and the subsequent meetings, Zhou’s principal goal was to persuade Kissinger to agree to “recognize the PRC as the sole legitimate government in China” and “Taiwan Province” as “an inalienable part of Chinese territory which must be restored to the motherland,” from which the U.S. must “withdraw all its armed forces and dismantle all its military installations.” (Since the Communists’ triumph in the Chinese civil war in 1949, the island of Taiwan had been the last outpost of the nationalist Kuomintang. And since the Korean War, the U.S. had defended its autonomy.)

With his eyes on so many prizes, Kissinger was prepared to make the key concessions the Chinese sought. “We are not advocating a ‘two China’ solution or a ‘one China, one Taiwan’ solution,” he told Zhou. “As a student of history,” he went on, “one’s prediction would have to be that the political evolution is likely to be in the direction which [the] Prime Minister … indicated to me.” Moreover, “We can settle the major part of the military question within this term of the president if the war in Southeast Asia [i.e. Vietnam] is ended.”

Asked by Zhou for his view of the Taiwanese independence movement, Kissinger dismissed it out of hand. No matter what other issues Kissinger raised — Vietnam, Korea, the Soviets — Zhou steered the conversation back to Taiwan, “the only question between us two.” Would the U.S. recognize the People’s Republic as the sole government of China and normalize diplomatic relations? Yes, after the 1972 election. Would Taiwan be expelled from the United Nations and its seat on the Security Council given to Beijing? Again, yes.

Fast forward half a century, and the same issue — Taiwan — remains Beijing’s No. 1 priority. History did not evolve in quite the way Kissinger had foreseen. True, Nixon went to China as planned, Taiwan was booted out of the U.N. and, under President Jimmy Carter, the U.S. abrogated its 1954 mutual defense treaty with Taiwan. But the pro-Taiwan lobby in Congress was able to throw Taipei a lifeline in 1979, the Taiwan Relations Act.

The act states that the U.S. will consider “any effort to determine the future of Taiwan by other than peaceful means, including by boycotts or embargoes, a threat to the peace and security of the Western Pacific area and of grave concern to the United States.” It also commits the U.S. government to “make available to Taiwan such defense articles and … services in such quantity as may be necessary to enable Taiwan to maintain a sufficient self-defense capacity,” as well as to “maintain the capacity of the United States to resist any resort to force or other forms of coercion that would jeopardize the security, or the social or economic system, of the people on Taiwan.”

For the Chinese hedgehog, this ambiguity — whereby the U.S. does not recognize Taiwan as an independent state but at the same time underwrites its security and de facto autonomy — remains an intolerable state of affairs.

Yet the balance of power has been transformed since 1971 — and much more profoundly than Kissinger could have foreseen. China 50 years ago was dirt poor: despite its huge population, its economy was a tiny fraction of U.S. gross domestic product. This year, the International Monetary Fund projects that, in current dollar terms, Chinese GDP will be three quarters of U.S. GDP. On a purchasing power parity basis, China overtook the U.S. in 2017.

In the same time frame, Taiwan, too, has prospered. Not only has it emerged as one of Asia’s most advanced economies, with Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co. the world’s top chip manufacturer. Taiwan has also become living proof that an ethnically Chinese people can thrive under democracy. The authoritarian regime that ran Taipei in the 1970s is a distant memory. Today, it is a shining example of how a free society can use technology to empower its citizens — which explains why its response to the Covid-19 pandemic was by any measure the most successful in the world (total deaths: 10).

As Harvard University’s Graham Allison argued in his hugely influential book, “Destined for War: Can America and China Escape Thucydides’s Trap?”, China’s economic rise — which was at first welcomed by American policymakers — was bound eventually to look like a threat to the U.S. Conflicts between incumbent powers and rising powers have been a feature of world politics since 431 BC, when it was the “growth in power of Athens, and the alarm which this inspired in Sparta” that led to war. The only surprising thing was that it took President Donald Trump, of all people, to waken Americans up to the threat posed by the growth in the power of the People’s Republic.

Trump campaigned against China as a threat mainly to U.S. manufacturing jobs. Once in the White House, he took his time before acting, but in 2018 began imposing tariffs on Chinese imports. Yet he could not prevent his preferred trade war from escalating rapidly into something more like Cold War II — a contest that was at once technological, ideological and geopolitical. The foreign policy “blob” picked up the anti-China ball and ran with it. The public cheered them on, with anti-China sentiment surging among both Republicans and Democrats.

Trump himself may have been a hedgehog with a one-track mind: tariffs. But under Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, U.S. policy soon reverted to its foxy norm. Pompeo threw every imaginable issue at Beijing, from the reliance of Huawei Technologies Co. on imported semiconductors, to the suppression of the pro-democracy movement in Hong Kong, to the murky origins of Covid-19 in Wuhan.

Inevitably, Taiwan was added to the list, but the increased arms sales and diplomatic contacts were not given top billing. When Richard Haass, the grand panjandrum of the Council on Foreign Relations, argued last year for ending “strategic ambiguity” and wholeheartedly committing the U.S. to upholding Taiwan’s autonomy, no one in the Trump administration said, “Great idea!”

Yet when Pompeo met the director of the Communist Party office of foreign affairs, Yang Jiechi, in Hawaii last June, guess where the Chinese side began? “There is only one China in the world and Taiwan is an inalienable part of China. The one-China principle is the political foundation of China-U.S. relations.”

So successful was Trump in leading elite and popular opinion to a more anti-China stance that President Joe Biden had no alternative but to fall in line last year. The somewhat surprising outcome is that he is now leading an administration that is in many ways more hawkish than its predecessor.

Trump was no cold warrior. According to former National Security Adviser John Bolton’s memoir, the president liked to point to the tip of one of his Sharpies and say, “This is Taiwan,” then point to the Resolute desk in the Oval Office and say, “This is China.” “Taiwan is like two feet from China,” Trump told one Republican senator. “We are 8,000 miles away. If they invade, there isn’t a f***ing thing we can do about it.”

Unlike others in his national security team, Trump cared little about human rights issues. On Hong Kong, he said: “I don’t want to get involved,” and, “We have human-rights problems too.” When President Xi Jinping informed him about the labor camps for the Muslim Uighurs of Xinjiang in western China, Trump essentially told him “No problemo.” On the 30th anniversary of the 1989 Tiananmen Square massacre, Trump asked: “Who cares about it? I’m trying to make a deal.”

The Biden administration, by contrast, means what it says on such issues. In every statement since taking over as secretary of state, Antony Blinken has referred to China not only as a strategic rival but also as violator of human rights. In January, he called China’s treatment of the Uighurs “an effort to commit genocide” and pledged to continue Pompeo’s policy of increasing U.S. engagement with Taiwan. In February, he gave Yang an earful on Hong Kong, Xinjiang, Tibet and even Myanmar, where China backs the recent military coup. Earlier this month, the administration imposed sanctions on Chinese officials it holds responsible for sweeping away Hong Kong’s autonomy.

In his last Foreign Affairs magazine article before joining the administration as its Asia “tsar,” Kurt Campbell argued for “a conscious effort to deter Chinese adventurism … This means investing in long-range conventional cruise and ballistic missiles, unmanned carrier-based strike aircraft and underwater vehicles, guided-missile submarines, and high-speed strike weapons.” He added that Washington needs to work with other states to disperse U.S. forces across Southeast Asia and the Indian Ocean and “to reshore sensitive industries and pursue a ‘managed decoupling’ from China.”

In many respects, the continuity with the Trump China strategy is startling. The trade war has not been ended, nor the tech war. Aside from actually meaning the human rights stuff, the only other big difference between Biden and Trump is the former’s far stronger emphasis on the importance of allies in this process of deterring China — in particular, the so-called Quad the U.S. has formed with Australia, India and Japan. As Blinken said in a keynote speech on March 3, for the U.S. “to engage China from a position of strength … requires working with allies and partners … because our combined weight is much harder for China to ignore.”

This argument took concrete form last week, when Campbell told the Sydney Morning Herald that the U.S. was “not going to leave Australia alone on the field” if Beijing continued its current economic squeeze on Canberra (retaliation for the Australian government’s call for an independent inquiry into the origins of the pandemic). National Security Adviser Jake Sullivan has been singing from much the same hymn-sheet. Biden himself hosted a virtual summit for the Quad’s heads of state on March 12.

The Chinese approach remains that of the hedgehog. Several years ago, I was told by one of Xi’s economic advisers that bringing Taiwan back under the mainland’s control was his president’s most cherished objective — and the reason he had secured an end to the informal rule that had confined previous Chinese presidents to two terms. It is for this reason, above all others, that Xi has presided over a huge expansion of China’s land, sea and air forces, including the land-based DF‑21D missiles that could sink American aircraft carriers.

While America’s multitasking foxes have been adding to their laundry list of grievances, the Chinese hedgehog has steadily been building its capacity to take over Taiwan. In the words of Tanner Greer, a journalist who writes knowledgably on Taiwanese security, the People’s Liberation Army “has parity on just about every system the Taiwanese can field (or buy from us in the future), and for some systems they simply outclass the Taiwanese altogether.” More importantly, China has created what’s known as an “Anti Access/Area Denial bubble” to keep U.S. forces away from Taiwan. As Lonnie Henley of George Washington University pointed out in congressional testimony last month, “if we can disable [China’s integrated air defense system], we can win militarily. If not, we probably cannot.”

As a student of history, to quote Kissinger, I see a very dangerous situation. The U.S. commitment to Taiwan has grown verbally stronger even as it has become militarily weaker. When a commitment is said to be “rock-solid” but in reality has the consistency of fine sand, there is a danger that both sides miscalculate.

I am not alone in worrying. Admiral Phil Davidson, the head of U.S. forces in the Indo-Pacific, warned in his February testimony before Congress that China could invade Taiwan by 2027. Earlier this month, my Bloomberg Opinion colleague Max Hastings noted that “Taiwan evokes the sort of sentiment among [the Chinese] people that Cuba did among Americans 60 years ago.”

Admiral James Stavridis, also a Bloomberg Opinion columnist, has just published “2034: A Novel of the Next World War,” in which a surprise Chinese naval encirclement of Taiwan is one of the opening ploys of World War III. (The U.S. sustains such heavy naval losses that it is driven to nuke Zhanjiang, which leads in turn to the obliteration of San Diego and Galveston.) Perhaps the most questionable part of this scenario is its date, 13 years hence. My Hoover Institution colleague Misha Auslin has imagined a U.S.-China naval war as soon as 2025.

In an important new study of the Taiwan question for the Council on Foreign Relations, Robert Blackwill and Philip Zelikow — veteran students and practitioners of U.S. foreign policy — lay out the four options they see for U.S. policy, of which their preferred is the last:

The United States should … rehearse — at least with Japan and Taiwan — a parallel plan to challenge any Chinese denial of international access to Taiwan and prepare, including with pre-positioned U.S. supplies, including war reserve stocks, shipments of vitally needed supplies to help Taiwan defend itself. … The United States and its allies would credibly and visibly plan to react to the attack on their forces by breaking all financial relations with China, freezing or seizing Chinese assets.

Blackwill and Zelikow are right that the status quo is unsustainable. But there are three core problems with all arguments to make deterrence more persuasive. The first is that any steps to strengthen Taiwan’s defenses will inevitably elicit an angry response from China, increasing the likelihood that the Cold War turns hot — especially if Japan is explicitly involved. The second problem is that such steps create a closing window of opportunity for China to act before the U.S. upgrade of deterrence is complete. The third is the reluctance of the Taiwanese themselves to treat their national security with the same seriousness that Israelis take the survival of their state.

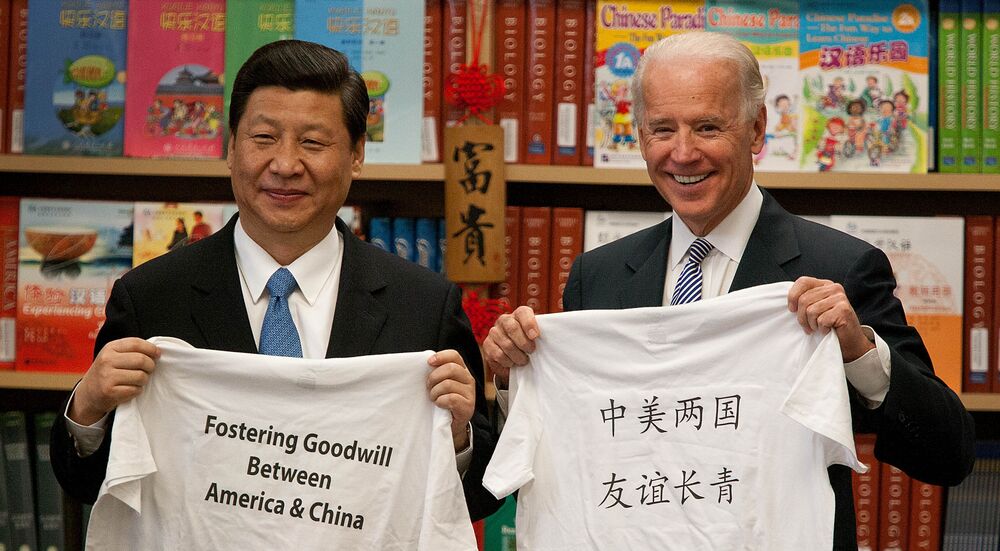

Thursday’s meeting in Alaska between Blinken, Sullivan, Yang and Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi — following hard on the heels of Blinken’s visits to Japan and South Korea — was never likely to restart the process of Sino-American strategic dialogue that characterized the era of “Chimerica” under George W. Bush and Barack Obama. The days of “win-win” diplomacy are long gone.

During the opening exchanges before the media, Yang illustrated that hedgehogs not only have one big idea – they are also very prickly. The U.S. was being “condescending,” he declared, in remarks that overshot the prescribed two minutes by a factor of eight; it would do better to address its own “deep-seated” human rights problems, such as racism (a “long history of killing blacks”), rather than to lecture China.

The question that remains is how quickly the Biden administration could find itself confronted with a Taiwan Crisis, whether a light “quarantine,” a full-scale blockade or a surprise amphibious invasion? If Hastings is right, this would be the Cuban Missile Crisis of Cold War II, but with the roles reversed, as the contested island is even further from the U.S. than Cuba is from Russia. If Stavridis is right, Taiwan would be more like Belgium in 1914 or Poland in 1939.