President Biden’s executive order calling for the eventual elimination of the use of private prisons by the federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP) serves as a hasty and misguided attempt to satisfy a political impulse without actually improving federal correctional services.

In fact, the new executive order could make conditions in prisons worse for inmates and staff. The Biden executive order repeats many of the same flawed arguments former President Barack Obama’s then-Assistant Attorney General Sally Yates made in an August 2016 memothat coincided with the release of an Office of the Inspector General (OIG) report. At that time Yates said:

“Private prisons … simply do not provide the same level of correctional services, programs, and resources; they do not save substantially on costs; and as noted in a recent report by the Department‘s Office of the lnspector General, they do not maintain the same level of safety and security. The rehabilitative services that the Bureau provides, such as educational programs and job training, have proved difficult to replicate and outsource—and these services are essential to reducing recidivism and improving public safety.”

The biggest sticking point of the Yates memo was the allegation that private prisons in the Bureau of Prisons perform poorly when compared to their BOP-operated counterparts. This allegation does not have a basis in the OIG report itself, but it is nonetheless parroted by the new Biden administration’s EO, which says:

“(A)s the Department of Justice’s Office of Inspector General found in 2016, privately operated criminal detention facilities do not maintain the same levels of safety and security for people in the Federal criminal justice system or for correctional staff.”

As I noted in a report released in 2017, despite Yates’, and now Biden’s strong claims, there’s no evidence, that privately-run BOP prisons are less safe or provide inferior service compared to the BOP’s “in-house” prisons. In fact, the BOP warned against making such comparisons in a response to an earlier draft of the August 2016 OIG report:

“(W)e continue to caution against drawing comparisons of contract prisons to BOP operated facilities as the different nature of the inmate populations and programs offered in each facility limit such comparisons.”

Despite this clear warning from the BOP itself saying not to use the August 2016 OIG report to compare public and private prisons against each other due to the numerous factors that make such comparisons untenable, many continue to do so.

When sample groups share similar characteristics, comparisons tend to be more valid. But the Bureau of Prisons overwhelmingly puts foreign prisoners (mostly from Mexico and a few Central American countries) in privately-run BOP prisons, while the BOP-operated prisons are overwhelmingly filled with Americans. While the distinction may seem subtle, communicating with a mostly non-English speaking population presents additional costs and challenges for the operation of those prisons. Communication with a mostly Spanish-speaking population requires additional staff resources that add costs to operating the facilities. In addition to the communication barriers, there can be other problems related to the prisons having a lack of background information on the inmates themselves. Having a clearer criminal background of inmate populations helps corrections officers plan housing arrangements to minimize potential conflicts. When a prison knows of potential affiliations with hate groups, gang affiliations, and the like, it is available to better inform such decisions.

This segregated approach also can affect the safety of inmates and staff. The placement of inmates in cells is usually coordinated to avoid potential violent confrontations, so confining one large subset of inmates to one type of prison makes that sort of planning more difficult. The authors of the OIG report make those points pretty clearly:

“We acknowledge that inmates from different countries or who are incarcerated in various geographical regions may have different cultures, behaviors, and communication methods. The BOP stated that incidents in any prison are usually a result of a conflict of cultures, misinterpreting behaviors, or failing to communicate well. One difference within a prison housing a high percentage of non-U.S. citizens is the potential number of different languages and, within languages, different dialects. Without the BOP conducting an in-depth study into the influence of such demographic factors on prison incidents, it would not be possible to determine their impact.”

One way to better ensure safety, equality, and facilitate comparisons between the BOP’s public and private prisons would be to integrate the native Spanish-speaking population into all BOP facilities, so all BOP prisons would have a similar mix of native English and Spanish speakers. The added diversity would force BOP-run prisons to account for serving an entirely new set of inmates in terms of background, while the added ability to separate and strategically place inmates could help to minimize potentially violent incidents in all facilities. Providing services for inmates to a meaningful level of satisfaction is difficult for any prison operator, and it is made even more difficult when language barriers are introduced. Equalizing populations would also force the Bureau of Prisons to undertake those challenges itself, which it will eventually have to do anyway if private prisons are eliminated in the BOP.

Another problem that prevents valid comparisons between public and private prisons in the BOP is the lack of assurance that the two prison types have equal levels of security and monitoring procedures. While both public and private BOP prisons have dedicated resources to monitoring the operations and safety of their facilities, the Bureau of Prisons serving as both operator and monitor in its own facilities raises concerns about the comparability of the operational and monitoring regimes of public and private prisons in the BOP.

The August 2016 report does note that a greater number of security incidents per capita in privately-run BOP prisons, but in addition to communication barriers and other factors that make ensuring safety and security more difficult in contract prisons, there is reason to believe that publicly-run BOP prisons also have problems implementing staff policies and changes related to safety. Far from conclusive and limited to contraband interdiction, the BOP OIG’s own findings at least suggest a culture of distrust exists between staff and management in BOP-operated prisons, hindering opportunities to accurately assess and identify problems, much less improve and innovate practices and procedures in response to those problems.

Another OIG report produced in June 2016, which focused mostly on conducting staff contraband searches in BOP-operated prisons, noted that searching BOP staff at recommended levels has long been a struggle. The June 2016 report notes the BOP was asked to implement recommended staff search procedure changes in 2006, calling on all facilities to randomly search at least five percent of their staff on a monthly basis, only for the BOP prison guard union to stall and avoid implementation. After nearly a decade, it has implemented the policy inadequately and unevenly. The contraband interdiction report notes only one percent of employee shifts had received any pat-down searches between January and June of 2014, and the searches themselves did not follow established protocol for conducting proper searches (which should take two minutes per person, despite at least one search event lasting only a single minute).

While the BOP says that they were not finding contraband in the prisons they operate in-house, the OIG makes it clear that they doubt the validity of their self-reported claims:

“(I)n light of the BOP’s infrequent application of random pat search events and other related issues described in this report, the absence of contraband recoveries may not constitute an accurate performance measure.”

Since the contraband interdiction report’s time span coincides with the August 2016 report’s period of reporting incidents, the OIG seems to be saying that at least some of the contraband numbers reported from BOP-run prisons in their subsequent August report may be inaccurate. And the BOP’s in-house contraband interdiction efforts do not seem to be improving much. According to an OIG report from last year intended to map out the agency’s largest performance challenges, contraband is still a “pervasive problem” in BOP prisons. The report says that “5 of the 11 recommendations (from the 2016 contraband interdiction report) remain open, including those related to revising its contraband staff search policy and upgrading its security camera system.”

In contrast, the August 2016 OIG report’s authors do note that the relationship between BOP and private prison company staff (for the oversight and monitoring of contracts) is one that effectively works to improve conditions as problems are confronted:

“We determined that for each of the safety and security-related deficiencies that BOP onsite monitors identified during our study period, the contractor responded to the BOP and took corrective actions to ensure the prison was in compliance with policies and the contract.”

While one cannot conclude that guard searches are not an issue in privately-run BOP prisons, the OIG’s findings show that guard searches remain a big problem in the BOP’s publicly run prisons, despite over a decade of warnings and recommendations from the OIG to improve things. The August 2016 OIG report, in contrast, provides examples of how private BOP prisons changed procedures in immediate response to problems, including improving the interdiction of contraband as well as health care procedures, recordkeeping, and staffing procedures. None of these changes took contracted facilities a decade to implement fully.

The Biden executive order also creates problems on the training, educational and rehabilitation side of corrections. “We must ensure that our nation’s incarceration and correctional systems are prioritizing rehabilitation and redemption,” the order says.

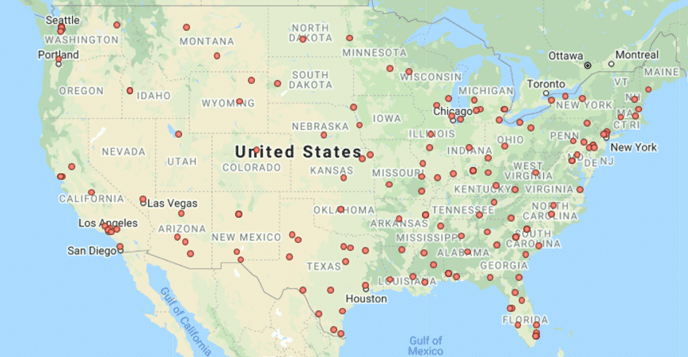

The BOP itself is currently entered into over 150 contracts with private entities (businesses and nonprofits) for reentry services alone, with centers scattered all over the United States, mostly in or near medium-to-large cities (100,000+). Some of those firms are the same ones that operate reentry facilities, and a new anti-contracting would certainly undermine BOP’s goals on reentry.

Map of Reentry Centers Contracted By the Bureau of Prisons:

GEO and CoreCivic, two companies that manage federal prisons, alone combine for 17 contract facilities that accommodate around 13 percent of the BOP’s total capacity of roughly 9,800 inmates. The 2016 Yates memo chides private prison companies for preventing the reduction of inmate recidivism, even as the BOP continues to rely on these same companies for reentry services.

Prioritizing rehabilitation and redemption in the BOP would undoubtedly include finding the best reentry services and facilities for those transitioning back into society. Banning private prison companies from the equation only ensures that the BOP would be forced to eliminate some of the very arrangements it sees as providing the best answers to the difficult questions of preparing inmates for the final steps of returning to life as citizens.

Few question that prison systems in the United States need significant reforms and changes. Many are finally starting to come to the conclusion that the so-called tough-on-crime mentality has done more harm than good, including in terms of making conditions worse for inmates while in prison and subsequently after their release. Some of these failures have reached the point where federal consent decrees in multiple states have been filed in recent decades that cite prison conditions that violate our Constitution’s protections against cruel and unusual punishment.

But solutions to improving life inside and after prison have largely remained elusive to governments. Radical and innovative thinking will be needed to improve prison conditions to be more in line with best practices that have been demonstrated in Australia and New Zealandthrough effective use of performance-based contracting where private prison funding levels are tied to reducing recidivism.

A move toward a more rehabilitative and constructive incarceration experience requires policy changes that move away from the real driving factors of mass incarceration. After decades of courts, politicians, and prosecutors making incarceration harsher and lengthier, a growing consensus is moving toward a more rehabilitative approach that recognizes most inmates will eventually be released and reenter society.

New approaches focus on building inmates’ work and personal skills to help them avoid a return to prison. Innovative and competition-driven corrections services can help make that happen, and such a transformation requires departments of corrections that seek to find solutions wherever they emerge.

Getting prison operators and service providers the right incentives to work toward effective solutions should be the focus of the Bureau of Prisons and state departments of correction, regardless of whether the individuals’ responsible work for the government or private sector.

In the corrections space, reform should hinge on improving health and safety conditions as well as the availability of opportunities for inmates while in prison and after release. That is not what government-run prisons have delivered, and expecting that to change without competition from the private sector ignores how the present situation in corrections has played out for decades.

Given the BOP’s reliance on the private sector, a working relationship with private operators who provide effective rehabilitative and reentry services seems crucial. So let’s continue to develop ways to hold all prisons accountable to similar standards, no matter who runs them, and try to find what works best to ensure inmates and staff are kept in safe, secure environments that provide opportunities for those inmates to improve their lives behind bars and after their release. Looking to end private prisons in no way simplifies the difficult problems facing corrections, and the Biden administration’s proposed ban would, unfortunately, work to make solutions more elusive.